Canada, Earth

Flag

The adoption of the national flag of Canada was the culmination of many years of discussion, thousands of designs and a heated debate in Parliament. The search began in 1925 when a Committee of the Privy Council began to investigate potential designs. In 1946, a parliamentary committee examined more than 2,600 submissions but could not reach agreement on a new design. As the centennial of Confederation approached, Parliament increased its efforts to choose a new flag. On February 15, 1965, the national flag of Canada was raised for the first time over Parliament Hill.

The flag is red and white, the official colours of Canada, with a stylized eleven-point maple leaf at its centre. The flag's proportions are two by length and one by width. The red-white-red pattern is based on the flag of the Royal Military College and the ribbon of the General Service Medal of 1899, a British decoration given to those who defended Canada in 19th-century battles.

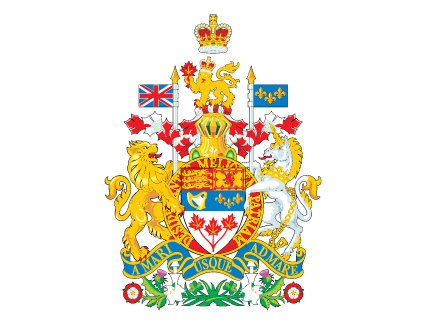

Coat of Arms

Origin of the Name

The name Canada likely comes from the Huron-Iroquois word "kanata", meaning village or settlement. In 1535, two Aboriginal youths told French explorer Jacques Cartier about the route to "Kanata" site of present-day Québec City. Cartier used the word "Canada" to describe not only the village but the entire area controlled by its chief. The name was soon applied to a much larger area: maps in 1547 designated everything north of the St. Lawrence River as "Canada."

Canada's Colours

“It would certainly seem that the Maple Leaf... is pre-eminently the proper badge to appear on our flag.”

The colors on the Canadian flag were not chosen on a whim. King George V declared red and white to represent Canada in 1921. He chose red to signify Saint George’s cross and white to symbolize the French royal emblem at the time. The combination of white and red also was used in the General Service Medal which was issued by Queen Victoria. Major General Eugene Fiset stated that Canada's emblem should be a solitary red maple leaf against a white field. The maple leaf had been worn by Olympic athletes in Canada since 1904 and had been the unofficial symbol of Canada since 1836, when it was adopted as the official emblem of The St. Jean Baptiste Society of Lower Canada.

History

Today Canada is made up of ten provinces and three territories. On July 1st, 1867 when the British North America Act created the new Dominion of Canada, there were only four provinces, Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick.

Three years after Confederation in 1870, Canada purchased Rupert's Land from the Hudson's Bay Company, which had been granted a charter to the area by the British government exactly two centuries earlier. Rupert's Land spanned all land drained by rivers flowing into Hudson's Bay, roughly 40% of present-day Canada. The selling price was 300,000 pounds sterling.

Also in 1870, Britain transferred the North-Western Territory to Canada. Previously, the Hudson's Bay Company had an exclusive license to trade in this area, which stretched west to the colony of British Columbia and north to the Arctic Circle. When it was discovered in the mid 1800s that the prairies had enormous farming potential, the British government refused to renew the company's license. With the Hudson's Bay Company out of the area, Britain was free to turn the land over to Canada.

Rupert's Land and the North-Western Territory were combined to form the Northwest Territories. The Manitoba Act of 1870 created the province of Manitoba from a small portion of this land.

In 1871 British Columbia joined the union with the promise of a railway to link it to the rest of the country.

In 1873, Prince Edward Island, which had previously declined an offer to join Confederation, became Canada's seventh province.

Yukon, which had been a district of the Northwest Territories since 1895, became a separate territory in 1898.

Meanwhile, Canada was opening up its west. Migrants from eastern Canada and immigrants from Europe began to settle in the prairies, which were still part of the Northwest Territories. Then, in 1905, the provinces of Saskatchewan and Alberta were created, completing the map of Western Canada.

After great debate and two referenda, the people of Newfoundland and Labrador voted to join Confederation in 1949, creating Canada's tenth province.

In 1999, Nunavut was created from the eastern portion of the Northwest Territories to complete what is now present-day Canada.

Years in which Provinces and Territories joined Confederation:

- 1867 — Ontario - Quebec - Nova Scotia - New Brunswick

- 1870 — Northwest Territories - Manitoba

- 1871 — British Columbia

- 1873 — Prince Edward Island

- 1898 — Yukon

- 1905 — Saskatchewan - Alberta

- 1949 — Newfoundland and Labrador

- 1999 — Nunavut

History of the Maple Leaf

By Rick Archbold

Canada's flag is no arbitrary emblem. It is the natural culmination of a complex historical process that began long before Confederation. The flag's attractive, stylized sugar maple leaf embodies the history of the place now called Canada from the first European contact with our native peoples to the present day—and its symbolism continues to grow richer as our country evolves. In short, the story of the Maple Leaf is the story of Canada.

The beginning of the story has been lost, so we must imagine it. It began the first time a newcomer chose to identify himself with a symbol native to his new homeland instead of one of the nostalgic images of the Old Country. Perhaps it was a beaver—the animal that powered the Canadian economy for much of our history before 1867—or maybe it was a canoe—the main mode of transportation until the early 19th century. Inevitably among these early home-grown symbols was the sugar maple leaf, which turns a brilliant scarlet in the autumn and is produced by a tree that yields a delicious, nourishing sap.

The maple leaf made its first documented appearance as a symbol of Canada in 1836, when it was adopted as the official emblem of The St.-Jean-Baptiste Society of Lower Canada. At the young society's annual banquet that year, its president said, "The maple is the king of our forest; it is the emblem of the Canadian people." English Canadians were quick to agree. During the 1860 visit to British North America of Edward Prince of Wales (the future Edward VIII), a maple leaf pin became the identity badge worn by native-born Canadians.

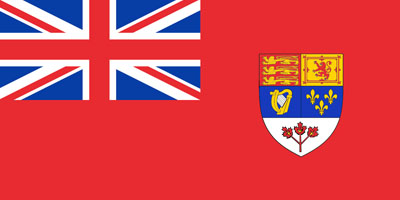

Yet in the years following Confederation in 1867, the flag that flew from the Peace Tower of Ottawa's new Parliament Buildings was something called the Canadian Red Ensign: a British red ensign (emblem of its merchant marine) "defaced in the fly" with the arms of the provinces. As new provinces joined up, the shield on outer half of the flag became more and more crowded. The problem was solved in 1928, when George V declared Canada's official colours to be red and white and granted us a coat of arms that included "three sugar maple leaves conjoined on a single stem." The much simpler shield from the Canadian coat of arms replaced the crowded provincial shield on the Canadian Red Ensign.

Trouble was, the Canadian ensign had no official status on Canadian soil. From Confederation until February 1965, Canada's only official national flag was Britain's Royal Union Flag, more popularly known as the Union Jack. During the first half of the 20th century, there were two attempts by Parliament to legislate a national flag and on each occasion, the Canadian Red Ensign was the clear front runner. But Quebec understandably objected to any flag whose primary symbol was the Union Jack (which occupies the area of a flag known as the upper hoist). Both attempts died in committee.

By the time Lester Pearson won the 1963 federal election, there were only two serious candidates for a national flag: some version of the Canadian Red Ensign; a flag with a sugar maple leaf or cluster as its main symbol. (The maple leaf had gained symbolic weight during two world wars, when almost every Canadian soldier wore it as a cap or collar badge.) During the campaign, Pearson had promised to give Canada its own flag during his first term. True to his word, in early June 1964, he introduced his proposed flag in the House of Commons: three conjoined red maple leaves on a white background flanked by two blue bars.

Many Canadians, especially those who belong to the younger generation and those who traced their ancestry to someplace other than the British Isles, liked the new flag. But a great number did not and their champion was John George Diefenbaker, recently deposed as Prime Minister and now Leader of the Opposition. Dief stood for those still wedded to "tradition", by which they meant the emblems of Britain and France. He opposed "Pearson's Pennant" every step of the way as the debate droned on through the long hot summer of 1964. As a last resort, in September an all party Flag Committee was appointed whose mandate was to recommend a flag design to the House in six weeks. Everyone assumed that the committee would be deadlocked and that yet again the quest for a national flag would end in stalemate.

Miraculously—with the help of some artful backroom maneuvering by the Liberals and the New Democrats on the committee—the Flag Committee voted unanimously for a red and white flag with a single maple leaf. After a final acrimonious debate in the House of Commons, the committee's design was adopted. Then it was substantively refined, notably by Jacques St.-Cyr, a graphic artist working for the federal government. It was St.-Cyr who came up with the elegant, simplified sugar maple leaf we know today. (Unlike the twenty-seven points on the real maple leaf, St.-Cyr's leaf has only eleven, yet it's unmistakably the leaf of a sugar maple.)

On February 15, 1965, from on a temporary flagpole erected next to a temporary dais in front of the Peace Tower, the Canadian Red Ensign was lowered for the last time and the new Maple Leaf Flag was raised. Only two years shy of its hundredth birthday, Canada had its own distinct and instantly recognizable national flag.

By Expo 67 and the coast-to-coast celebrations of Centennial year it was already hard to imagine Canada without the Maple Leaf. St-Cyr's stylish design was quickly incorporated into countless commercial brands and cleverly integrated into the federal government's graphic identity. Everywhere Canadians went, they were instantly recognized by their distinctive flag.

The Maple Leaf has grown with the country. In the process, it has come to represent the values of diversity and tolerance that represent the best of what 21st-century Canada offers the world.